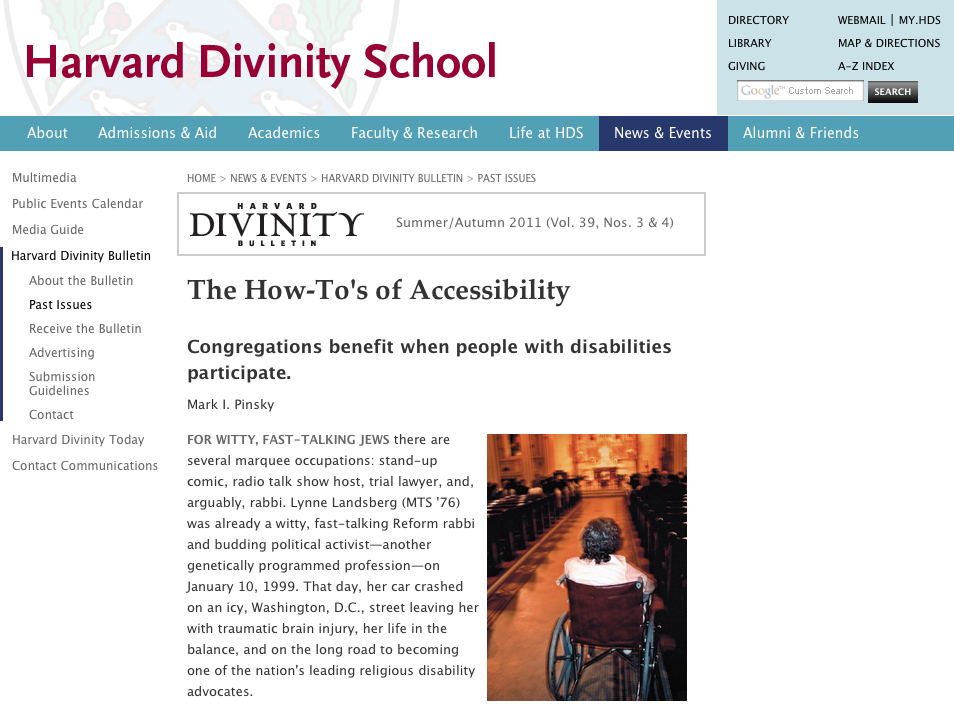

FOR WITTY, FAST-TALKING JEWS there are several marquee occupations: stand-up comic, radio talk show host, trial lawyer, and, arguably, rabbi. Lynne Landsberg (MTS '76) was already a witty, fast-talking Reform rabbi and budding political activist—another genetically programmed profession—on January 10, 1999. That day, her car crashed on an icy, Washington, D.C., street leaving her with traumatic brain injury, her life in the balance, and on the long road to becoming one of the nation's leading religious disability advocates.

FOR WITTY, FAST-TALKING JEWS there are several marquee occupations: stand-up comic, radio talk show host, trial lawyer, and, arguably, rabbi. Lynne Landsberg (MTS '76) was already a witty, fast-talking Reform rabbi and budding political activist—another genetically programmed profession—on January 10, 1999. That day, her car crashed on an icy, Washington, D.C., street leaving her with traumatic brain injury, her life in the balance, and on the long road to becoming one of the nation's leading religious disability advocates.

Landsberg made a vivid impression on her fellow students at Harvard Divinity School, as well as on her faculty adviser, Harvey Cox. Although she was the first of his students headed for the rabbinate, she was avid in her study of New Testament. "Of the hundreds, maybe thousands, of students I have taught over more than four decades at Harvard, she stands out and is in a class of her own," he recalls. "She was a superb student and a real class act," he says, "dazzling everyone with her looks and her charm and her brains."

Landsberg credits her journey from a near-fatal collision and near-total incapacitation to a grueling regimen of therapy, and to an upbeat outlook. "Brain injury recovery comes in small steps," she says, "like the first time I smiled in two years, which made my family ecstatic. If you keep a positive attitude and work as hard as your therapist tells you to, things will get better—but in smidgens."

In sermons and speeches (which still require rehearsals with her speech therapist), she also emphasizes the role of her religious faith and the support of her Jewish community. The three elements of that process, she explains, are: prayer, attentive visits, and practical support from congregations. It is an approach that is applicable to all faith traditions. On the road a good deal these days for the Reform movement's Religious Action Center (RAC), Landsberg maintains an almost precrash schedule: advocating legislation at Capitol Hill briefings for new members and staffers ("Nothing about Us without Us"); publicizing Jewish Disability Awareness Month, an effort that involves all branches of Judaism; appearing on panels; and writing op-ed columns. The speed of her speech—which now comes in bursts, with asides for wisecracks—can test the ability of a telephone interviewer to keep pace.

Landsberg worked with a Jewish disability coalition to help pass the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act, a more specific bill than the original 1990 landmark law, which deals with employment discrimination against people with disabilities. She is now busy—through the Interfaith Disability Advocacy Coalition (IDAC)—highlighting and defending those provisions of the 2010 Obama health care reform act that apply to people with disabilities. She is also campaigning to reform the way teachers can seclude and restrain children with disabilities through the proposed federal Keeping All Students Safe Act.

"I find her a model of courage, spirit, and humor," Cox says. "She laughs about her 'coma diet' in which she lost several pounds."

Like Landsberg, others have returned to ministry after devastating and debilitating injury and illness. If Chris Maxwell had lived in an earlier time, the viral encephalitis that wiped out his brain's capacity for short-term memory in 1996 would have effectively ended his pastorate. But with the assistance of modern medication and technology, the Assemblies of God pastor was able to return to the pulpit and the podium. In addition to traditional therapy, Maxwell can control his symptoms with drugs, and effectively outsource his memory to his Palm Pilot, which he downloads nightly to his computer's hard drive. Sermons and scriptural citations once delivered from memory are now made possible with the help of PowerPoint.

While technology enabled Maxwell to return to his congregation and most members welcomed him back and accepted his pastoral leadership, he acknowledges that he encountered another barrier. Some in his Pentecostal church thought less of him after he did not respond to healing by faith when hands were laid on him. So in 2006, Maxwell left the pulpit at Orlando's Evangel Assembly of God to become campus pastor and director of spiritual life at Emmanuel College in Franklin Springs, Georgia, his alma mater, and a motivational speaker and broadcaster.

As one blessed (thus far) with a reasonably unimpaired mind and body, I thought myself an unlikely choice to be asked to write a book about faith and disability, both physical and intellectual. But Richard Bass, head of the Alban Institute, the publisher, explained to me that funders wanted a book that would reach a general audience of clergy and people who may have no personal experience with disability, but who make the congregational decisions about accessibility and inclusion. And so I embarked on the research that led me to Landsberg, Maxwell, and many others, whose stories will be featured in the book Amazing Gifts: Stories of Faith, Disability and Inclusion, to be published later this year.

Although many religious leaders led the fight for the landmark Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, they also managed—for practical reasons, they said—to exempt houses of worship from most of its provisions. A majority of congregations have fewer than 125 members, making the cost of major architectural changes seem prohibitive. Negative attitudes toward people with disabilities create less visible but equally daunting barriers. If members of a small congregation see no one with an obvious disability, they may think there is no need to take action—not realizing who may have been left at home by the family in the next pew, or in a nearby group home, wanting to come if only they were made welcome. A 2010 survey by the Kessler Foundation and the National Organization on Disability found that people with disabilities are less likely to attend religious services at least once per month (50 percent compared to 57 percent for those without disabilities): the greater the disability, the less likely they are to attend.

"They can attend school, hold down jobs and turn the key in the door of their own apartments," wrote Erin R. DuBois in The Mennonite magazine. "They have won the legal battle for inclusion, but by the time they land in the pew at church, they may be too exhausted to fight for something more precious than their rights. Friendship is a gift the law can never guarantee to people with developmental disabilities. Churches across the United States, however, are reaping the rewards of building genuine relationships with those in their midst who are epitomized not by their disabilities but by their rare abilities to deepen the congregation's spiritual life."

Congregations have responded in a variety of ways. Some still wait until renovation or new construction enables them to make their facilities fully accessible. Others are like St. Michael the Archangel Catholic Church in Levittown, which, with the backing of the parish priest and the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, built a coalition of disability activists, seniors, and young families with strollers to raise more than $200,000 to build a new ramp to the sanctuary and an elevator to the basement social hall. At the other end of the spectrum, at East Goshen Mennonite Church in Indiana, all it took was a gifted woodworker to build a pull-out step for Barb Eiler, who was born with a bone disease that caused her short stature, which meant she couldn't be seen above the podium when she served as lector.

Sometimes no economic investment is necessary, and neither class nor race nor history is an insurmountable barrier. In the past year two accounts have appeared chronicling how young white men with disabilities in the South—one in the Mississippi Delta and another in Southside Virginia—found faith homes in black, working-class congregations.1 In each case, the young white men benefited from the African American tradition of accepting people in their brokenness, and the ecstatic Pentecostal worship tradition of people shouting, speaking in tongues, and falling to the floor after being "slain in the spirit." Despite their intellectual, emotional, and physical disabilities, they could fully participate without drawing disapproving stares.

In the course of my research, the biggest revelation has been that there are converging streams of demography, war, and science creating a wave of people in need, a wave that is about to break at the doors of our faith communities. Despite our never-ending efforts to beat the clock, my own huge cohort of Boomers is aging into infirmity—with all the attendant issues of hearing, vision, and mobility, not to mention mental acuity. At the same time, military veterans are returning from Iraq and Afghanistan with missing limbs, traumatic brain injury, and post-traumatic stress disorder. And advances in neonatal treatment mean that babies born with severe and multiple birth defects are—or soon will be—living into adulthood.

No faith tradition or denomination will be immune from these challenges. Increasingly, people with physical and intellectual disabilities are advocating for themselves and others, and asserting their rights to be full participants in every aspect of life, including their faith lives, with family, friends, and caregivers in support. Beyond a catalogue of congregational best practices, what is emerging from my interviews is a mosaic of stories that I hope will inform, instruct, and illustrate what can be done. At the same time, I am trying to focus at least as much on people who cope heroically as I do on those who conquer—as inspiring as those like Maxwell and Landsberg may be. One of the themes of these stories is that accessibility and acceptance have more to do with attitude and effort than with economics. I want people to read these stories and say: "We can do that in our congregation! I can do that!"

"Many religious organizations have yet to learn what many American families have learned," says the Reverend Joel Hunter, pastor of Northland Church, a large, nondenominational congregation in suburban Orlando with an extensive disabilities ministry. "That is, that the extra work it takes to accommodate those with obvious disabilities is the price of experiencing the kind of deep love and fulfillment that only comes with self-sacrifice."

There is a growing body of serious, theological considerations of disability.2 The same issues are also working their way into popular culture, reaching larger and broader audiences in the process. Inspiration is the preferred narrative. In 2000, the Disney Channel aired a made-for-TV movie, Miracle in Lane 2, starring Frankie Muniz. The heart-tugging feature, later released on DVD, is based on the true story of Justin Yoder, a thirteen-year-old boy with spina bifida and hydrocephalus, who prays for some way to triumph and, in the process of doing so, has a vision of heaven that includes people in winged wheel chairs.

Humor can be helpful, although it can also be disquieting. The late John Callahan, who was paralyzed from the neck down in a drunk-driving auto crash at the age of twenty-one, went on to a lengthy and successful career as a magazine cartoonist known for his exceptionally mordant view of life with a disability. He titled one of his collections What Kind of God Would Allow a Thing Like This to Happen?

The theological issue of disability was front and center in a two-part South Park episode titled "Do the Handicapped Go to Hell?" and "Probably." The show's four main characters are upset after hearing a fiery sermon in their Catholic church about hell "for those who do not accept Christ." Timmy, one of their friends, has severe cerebral palsy and is unable to say more than his first name. After consulting their clueless priest, the main characters fear Timmy will not be able to go to confession or participate in Holy Communion, and thus faces eternal damnation. "We can't let Timmy go to hell," says one of them. "We're going to have to do something," which in this case means baptizing their friend in a wintry front yard with a garden hose.

It is unlikely that when the prophet Isaiah wrote (11:6), "A little child will lead them," he had in mind one of South Park's pint-sized, potty-mouthed fourth graders. And yet, congregations may take the lesson about what caring friends can do to include people like Timmy in their faith communities.

Mark I. Pinsky, longtime religion writer for The Orlando Sentinel and the Los Angeles Times, is author of The Gospel According to The Simpsons and A Jew among the Evangelicals. His work appears in USA Today and The Wall Street Journal, and he reports for BBC Radio 4.

FIND THIS ARTICLE AT: http://www.hds.harvard.edu/news-events/harvard-divinity-bulletin/articles/the-how-tos-of-accessibility

A decade after Thomas Jefferson left office, the nation's third President started working on a project compiling the four gospels of the Bible's New Testament into a book that removed supernatural parts Jesus' life. It came to be known as "The Jefferson Bible." The work was recently published by the Smithsonian Institution. NPR affiliate WMFE invited a panel of religious leaders and scholars to discuss the meaning and impact of Jefferson's biblical revisions. Here, Pastor Joel Hunter talks about what happens to Christianity if miracles like the Virgin Birth and the Resurrection are removed from the faith. CLICK TO LISTEN.

A decade after Thomas Jefferson left office, the nation's third President started working on a project compiling the four gospels of the Bible's New Testament into a book that removed supernatural parts Jesus' life. It came to be known as "The Jefferson Bible." The work was recently published by the Smithsonian Institution. NPR affiliate WMFE invited a panel of religious leaders and scholars to discuss the meaning and impact of Jefferson's biblical revisions. Here, Pastor Joel Hunter talks about what happens to Christianity if miracles like the Virgin Birth and the Resurrection are removed from the faith. CLICK TO LISTEN.